For anyone who wants to kick-start their writing career, how do you craft an article that top publications would actually want to buy? Susan Shapiro says you have to make it sensational. Write a three-page, double-spaced essay about your darkest, most humiliating secret. Susan is an award-winning writer and professor. Today, she joins Robin Colucci to share a trick she has taught for 25 years with her students, many of whom are now successful authors. Join in the conversation and discover simple tips on how you can kick-start your author career by writing for top publications.

—

Watch the episode here:

Listen to the podcast here:

Simple Secrets To Kick-Start Your Author Career by Writing Articles for Top Publications with Susan Shapiro

I am pleased to introduce Susan Shapiro. She is an award-winning writing professor who freelances for The New York Times, New York Magazine, The Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times, Elle Magazine, The New Yorker, as well as Oprah Magazine. She is the bestselling author and co-author of seventeen books her family hates, like Five Men Who Broke My Heart, Lighting Up, Unhooked, The Forgiveness Tour, and a book I bought, the writing guide called The Byline Bible. She reveals techniques she’s perfected, sharing how to land impressive clips to start or relaunch your career.

Sue teaches her Instant Gratification Takes Too Long courses at The New School, NYU, Columbia University, and in private classes and seminars now offered online. She’s taught more than 25,000 students of all ages and backgrounds at NYU, Columbia Temple, The New School, and Harvard University. I want to share with you that Sue’s depth of experience, as well as the variety of her experiences, is gold. It’s what she’s about to share. This is so relevant not only for people who want to kickstart their writing career but also for the kinds of people that I work within my practice. They have a different career and want to launch their incarnation as an author. They want to transform from an expert and add that mantle of the author.

If you’re an author and you can write an article on your subject expertise and get it published in a major national venue like The New York Times or Washington Post or The New Yorker, then that makes you more appealing as an author if you are looking for that traditional book deal. Even if you haven’t thought about writing articles before, I strongly encourage you to pay close attention to what Sue has to say about how you craft an article that a major publication would want to buy. That can help you build your platform. She talks about how you craft articles once your book is out to keep your book front and center and in the conversation. There’s lots of gold here and lots to learn.

—

Susan, welcome to the show.

Thank you for having me.

I’m so excited to have you. As you know, my colleague, Sharon, has taken at least one class with you and has spoken so highly of you, so I feel privileged.

Sharon published a great piece.

It’s outstanding. I was so impressed. Now I get to talk to the master behind the student here, so this is great. Would you start off by telling our readers a little bit about your journey because you’ve authored how many books now?

If you count those co-authored books, I’m the author and co-author of seventeen books my family hates.

It also speaks volumes.

Be in an environment where you can get honest feedback. Share on XSeveral of them are about therapy, which explains how I was able to do it.

Let’s dive right in because that points to such a big concern, especially around nonfiction authors, people writing an essay or a memoir, and this anxiety, fear, and trepidation around, how do you write about difficult stuff? We’re going to go right into the deep end here, Sue. How do you write about the hard stuff?

First off, I come from a confessional poetry background. I studied at NYU at the time that I did my graduate degree. It was Joseph Brodsky, Yehuda Amichai, Sharon Olds, Louise Glück, and Galway Kinnell. They’re the most brilliant confessional writers you’ve ever met. I was schooled on the modern, so it was Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Robert Lowell, and Maya Angelou. Those are my gods. I came from that background. At a certain point, a mentor told me I had too many words and not enough music in my poetry. I was heartbroken, except for that he was an editor at The New York Times Magazine who started buying my essays and he thought there was more poetry in my prose than in my poems.

I took the same subjects that I’ve been delving into, studying and writing, which were the deepest, darkest secrets of my soul, and started writing essays about them. Those wound up being memoirs. The biggest insult Joseph Brodsky used to say to our class was, “There’s no blood here.” Luckily, my background encouraged deep, dark explorations. I have this great therapist who helped me quit smoking, drinking, and drugs. I said, “How do I stay healthy and successful?” He said, “Lead the least secret of life you can.” It might even justify the way that I think and write even more.

That’s in your The Byline Bible book.

I include the first assignment I had given my students for 25 years at NYU, The New School, and Columbia University. The first assignment I gave is, “Write three double-spaced typed pages about your most humiliating secret.” Those pieces have not only been published the best, so we’re talking New York Times, Wall Street Journal, New Yorker, New York Magazine, Harper’s, the best places in the world, but also, they have led to an amazing amount of books and even TV and film.

You finished Modern Love, right?

Yes. It led to books and podcasts. One student’s piece was in the TV show, but also books, movies, and TV series. In over 25 years of teaching, if somebody says to me, “I want to jump into publishing. I want to get a book deal. I want to start a career,” there’s no better way to launch it than a three double-spaced brilliant essay on writing about your most humiliating secret. Of course, there are ways to do it well and The Byline Bible definitely discusses ways to do it well and ways not. You never want it to be a victimized fetch about everything bad that everybody ever did to you. That tends to not work. One of my rules with good first-person writing is that you have to question, challenge, out, and trash yourself more than anybody else.

Over the years, not only has it been my preference, but then watching so many students get wildly successful. I wrote a humorous piece about what protégés owe mentors. I have so many students who’ve gotten a $500,000 book deal. I got a new piece about being jealous of my students who are getting these huge book, TV, and movie deals. There’s a lot of reasons why. I’ve certainly analyzed why these pieces are so successful. Sex sells and there tend to be sexy pieces or they’re provocative. A lot of my students have been in Modern Love, which is popular to go there and analyze what’s going on, whether it’s in terms of sexuality or mental health or addictions or family strife or fertility. There have been so many thousands of brilliant pieces my students have explored over the years. It’s a great thing to do.

For example, if somebody isn’t ready to write about something with #MeToo, rape, abuse, and all these heavy topics come up, I would never push somebody to publish something they aren’t ready for. There’s a lot of ways to make sure that what you’re writing has literary merit. Also, there are quite a few times where they advise somebody not to publish. One of my jokes is, don’t blow up your whole family for a $200 essay. If it’s a $200,000 memoir, let’s talk about it. If it’s a $200 essay, don’t do it.

Therein lies another question. How do you help somebody navigate where that line is? There’s got to be a whole spectrum.

I’ve been doing this for a lot of years. I have seventeen books out and I read a lot. I’m trying to keep up with 30 different books that students have published. I know this genre and I read all the newspapers and magazines that do personal essays. You absolutely need to be encouraged to tell your story and then have an environment where you’re getting honest criticism and feedback, whether it’s a classroom setting, which is great. I’ve been doing weirdly online and it exploded, so instead of only teaching in-person in New York, I’ve been doing private classes and seminars. All over the world, I get fascinating students. That works well.

Some people have beta readers or sensitivity readers that are colleagues. Some people can do it if they’re in a writing program or if they have other professors that they trust. Some people start their free writing groups. I’m in a lot of online groups and Facebook groups with writers. You can hire a ghost editor. There’s a lot of ways. In The Byline Bible, I laid out everything I taught in my classes for over 25 years. There are quite a few people who have read it, and then sent me an essay and said, “I did what you said and it came out in the Washington Post or The New York Times.” It’s exciting. If you read the book and you have absolutely no access to having anybody look at it, I even give people who are good for you to show in people who are not good. If somebody is going to say, “You’re so brilliant. This is amazing,” show it to somebody else.

That is so important because I found that writers, including myself, we’re not necessarily the best judge of your own work. Sometimes, people are way too harsh in some areas. They’re way too easy on themselves and others.

You definitely need critical feedback. I lay out the plan in The Byline Bible like, “Here’s the assignment.” Once you’ve gone through the things that make it more likely that you’ll get published, then you need to get feedback. In fact, I say the wrong way to do it is to finish something at 4:00 AM, decide it’s brilliant, and send it to The New Yorker. It’s not a good way to do it. There are a lot of ways that you could get honest feedback. I personally have two intense free writing workshops weekly that kill everything I write and I love it. They help me so much because the worst thing in the world is for you to think your piece is great and send it to an editor who doesn’t respond to you or hates it. It’s funny because they’ll say, “The first three paragraphs are boring.” I’ll be like, “Thank you,” because it helps me to know that.

One that I get quite often, which is also helpful is like, “You seem like a white, well-off bitch who I hate. You’re privileged and you’re not acknowledging it.” When I did my first book, Five Men Who Broke My Heart, my beta critics were saying, “You have this nice husband and you’re flirting with other people. We hate you.” It was extremely helpful advice because what happened was later in the book, there was an intensely emotional scene where I got two faxes on the same day. One is from my agent who tells me that the book I spent five years on has been rejected by the rest of the editors to whom she sent it to. The other one is the gynecologist saying how my husband and I will never be able to have children. I had a line that I felt like the agent was saying, “The only baby you have is ugly and we don’t want it.”

My writing group said, “Put that upfront. Put that in chapter one. Now we get you, like you, and understand your struggle. Now we’re more interested.” Sometimes, if you get criticism, there are easy ways to make your narrator more vulnerable or likable, or relatable. You need a good critic who can be honest with you and you have to be able to take criticism. If you can’t take criticism, then don’t do it. In fact, quite often, in The New York Times Modern Love column, I’ve had about 50 students break in there. The editors did not only critique and edit, but they will often show the piece to the person you wrote about to get their okay.

I saw that in your book, too. To make sure it’s factual.

If your ex or your ex-mother-in-law or your husband or your wife or spouse doesn’t want it to be published, they won’t publish it. You write something and you do the best you can, but you have to understand that it’s a collaborative process and editors and agents put their fingers all over it. You have to make sure that you’re ready for it. I’ve definitely had students who had a problem with that and I had to walk them through what the process is and make sure that they’re ready.

Many things you’re talking about are so relevant to people writing books, even if it’s not a memoir or essay, or when you’re writing a big idea thought leader book or a how-to book because there’s still that need for some vulnerability. A lot of times, experts who are writing books have this illusion that they need to look bulletproof and they need to be about the facts.

By being open to criticism, you discover what does the trick. Share on XEven fiction. I published four novels and I have a good overview. I do these online Sell Your Book classes where I have top editors and agents come in and they’re so helpful. It’s good to understand the market. I had a brilliant student who wanted to write a YA book. He was a gay Anglo man who wanted to write a lesbian Latino main character and the editors were like, “Don’t even go there. It’s not that it’s impossible.”

This was a YA novel. “It would make it so much harder to not have the protagonist be closer to your voice. Why even bother? If you haven’t finished the book, then there’s a choice. Why don’t you focus on the character’s own voice that’s the closest to you? You can have any characters you want, but don’t try to get in the head of someone that’s the opposite of you for no important reason.” One of the great things about opening yourself up to criticism, especially if it’s a teacher or a mentor or somebody older asking editors and agents, it helps you so much. I’ve had people take the five-week book class and they tell me that they learn more in ten hours than they did in ten years with undergrad and graduate in PhD degrees because, in academia, they don’t talk about publishing.

If they are, it’s a completely different kind of help because academic publishing is not what mass-market publishing is. One of the things I say to my clients is, “You have to remember, I don’t care what you’re writing. If you’re writing for the mass market, you’re in the entertainment industry first.” That is not true with academic writing, however.

You’re opening yourself up to a lot of things that you might not understand, which is why it’s so great to take a class, or maybe you could hire a coach. I always say to people, if they want to email me, I can recommend classes or writing coaches or ghost editors. There are a lot of ways available to get feedback on your work before you throw it out into the marketplace. Even if someone buys it, you have to make sure that it’s good. If you write something provocative, someone might want to publish it, but that doesn’t necessarily benefit you if it’s not good enough yet.

That is also true and that’s why the kind of feedback you’re getting is so important. One thing I’ve seen people do is to kick it over to their social networks, where it’s different to get feedback from somebody who knows what they’re talking about.

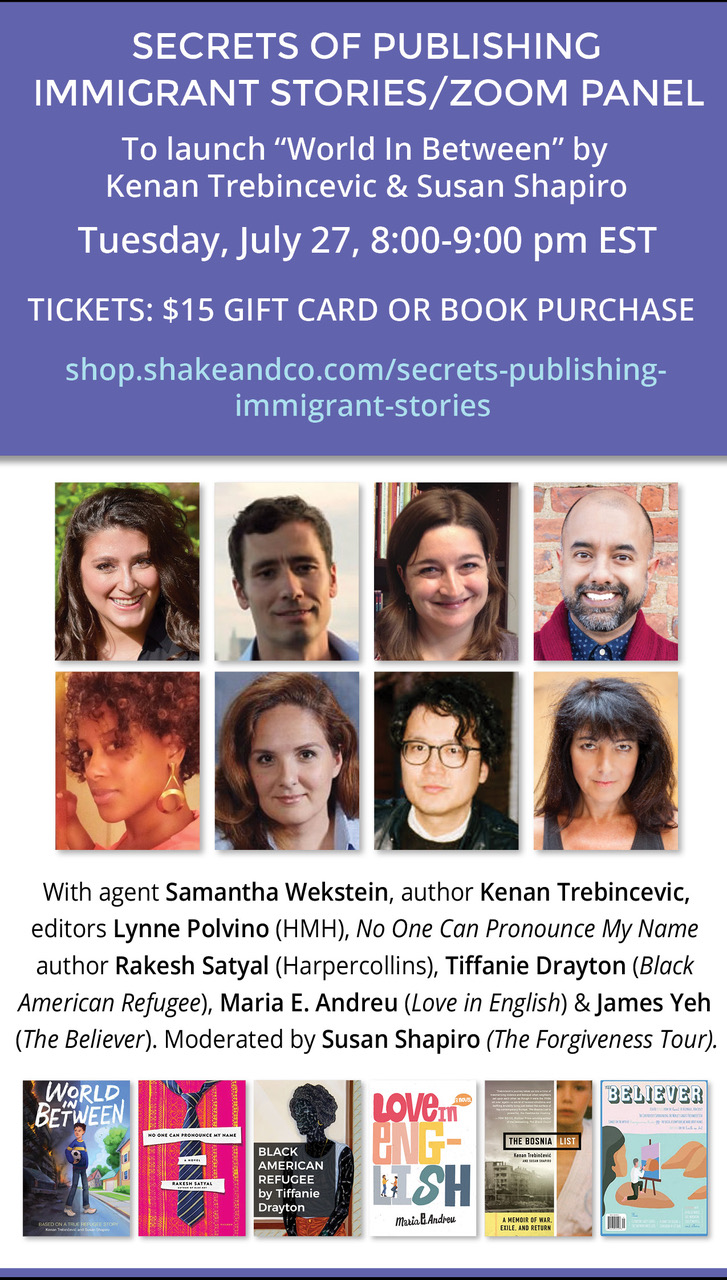

For example, I have a co-authored middle-grade novel from Houghton Mifflin called World in Between. It took me a long time to figure out this voice and I hired ghost editors who knew this genre well. In fact, my former student, Abby Sher, who’s this brilliant YA and MG writer, I needed somebody who’s done it before. I also hired Sharyn November, who is the head of kid’s books at Viking Penguin. I know brilliant editors who do nonfiction, adult fiction, and poetry, but I needed people that specifically understood this voice. I always recommend that if you want to publish something, you want to go to somebody who is an expert at that genre that’ll help you.

Something that you were talking about is kicking off your career as a writer by getting articles published. A lot of people come to us and they might be amazing experts, but they haven’t published yet, especially not in the mass market media. This is not only a tremendous idea for people who want to kick off their writing career but also for people who want to kick off their career in authorship.

I’m still teaching, but when I taught at NYU, The New School, and Columbia, I had an interesting mix of students. I would have MFA students, older students, 14 and 15-year-old high school students that were able to take my school of continuing ed class, and a 95-year-old take my class. In The Byline Bible, I boiled the specifics down for anybody who wants to do this. I’ve had a lot of doctors and lawyers take it who don’t understand the specific details you need for publishing in newspapers and magazines. I’ve had people who have MFA and PhD degrees who didn’t know anything about commercial publishing. I’ve also had people starting out in other fields who’ve never written anything. It works.

I’ve spent a lot of years analyzing and figuring out the 100 little stupid rules and things you have to understand if you had your piece published. I also say to my students that you get $100,000 worth of my therapy by osmosis. I’ve been doing it for so long that anything that could be screwed up, I screwed up, and then I went to therapy and flipped out. I got better critics, and then I figured out how to publish it. You get the benefit so that you don’t have to make the mistakes. I’m listing the mistakes that you want to avoid before you even start.

You seem to have a specific process for crafting and then going on to pitch an article.

It depends on what my goal is. They always say you’re supposed to write the book you wanted to read and teach the class you wanted to take. I did an undergraduate degree at the University of Michigan, and then a graduate degree at NYU, and nobody ever talked about publishing. It took me a lot of years. I worked at The New Yorker and I published in The New York Times. It took me years and years before I understood an overview. I have a great therapist. In fact, I wrote about him in a couple of my books. In Lighting Up, I wrote about how he helped me get rid of my self-destructive patterns and do more with my work.

I have this in The Byline Bible. It all comes down to what’s your goal? When somebody takes my class or seminar or context me, what’s your goal? For some people who’ve never been published, their goal is to be published. In that case, there’s a lot of places that maybe don’t pay, but that would get back to you right away and be all excited to publish your work. Maybe you get a clip and that launches your career. Maybe it goes viral and that could be great.

Some people want to launch a book, in which case that’s a different enamel when you have to write a certain piece and publish it in a certain place, usually in order to get editors interested. Some people come to me and say, “I’m broke and I just lost my job. I’m trying to make the most amount of money possible.” I’ve had students make as much as $5,000 for a piece. Especially with #MeToo and addictions, they want to come out in a certain way or they want to help other members of their community or they feel strongly about something and they want to do good in the world. They feel like writing about it would help.

There are all kinds of reasons why somebody would want to publish. I help my students with that, and then I have to figure that out myself. At a certain point, when I shifted from doing newspaper magazine work to wanting to promote books. I wake up in the morning and I work on a book project. I had a bestselling mentor and when I told him I had writer’s block, he said, “Plumbers don’t get plumber’s block. Don’t be self-indulgent. Just get to work every day.” He said to me, “A page a day is a book a year,” and that stayed with me. It turns out a page a day is more than a book a year.

I was going to say it would be a long book.

I definitely asked myself, “What’s my goal?” I have to do it every day and every week. Sometimes, my goal was to get a chapter ready for my writing group that I have at night. Sometimes, if I want to write an essay, I have to say to myself, “Is this going to benefit one of my books?” I asked the editors in advance whether they’d be able to do a link to one of my books. Sometimes, I intentionally pick the topic of one of my books because then, it benefits me. Sometimes, I’d start writing a piece and my writing group would say, “Don’t publish this piece now.” I won’t because I trust their judgment.

Especially with political subjects, Twitter wars, and stuff like that, there are times when I have books coming out where it doesn’t benefit me to step into any kind of political argument. I’ll sometimes step back and wait because I’m conscious of what’s going to benefit me and what could hurt me. Luckily, I can bring that to my students. I had somebody who was telling someone else’s story and she was telling a story that I felt was a little bit more of her daughter’s story than her story. I said, “I don’t necessarily think it’s going to benefit you to publish this right now. For a couple of hundred dollars, the harm that you could cause might not be worth it. Is there another topic where you’re doing good in the world or where you’re plugging your own book or where you can attain a goal that makes more sense?”

Something I wanted to circle back a little bit is related to this. When you talk about people wanting to write about certain issues like abuse or #MeToo, and things like that, that have been written about a great deal. How do you help people find that unique angle? How do you deal with that when it’s something that’s been written about a lot to make it so that a publication would say, “Let’s publish this also?”

There’s a lot of ways to do it depending on the piece and the topic. One of my secrets that I give away in The Byline Bible right away is, is it timely? What you want to do is you want to find something in the news that connects with what you’re writing about. Sometimes, maybe it’s worth reshaping your piece based on what’s going on in the culture. For example, I was working on a piece about how I had a couple of students who got $500,000 advances and I was jealous of my own students. I always think provocative is good. You’re supposed to write the thing that no one else will write.

It’s Arthur Miller who said something to the effect of, “The only thing worth writing about is the unspeakable.” I knew that was a good subject to write about, but when I’m in the middle of doing it, it turns out there were two famous novelists who were having a huge falling out on Twitter, a feud. We used that as my lead and all of a sudden, my own mentor-protégé story became more of a comment on what’s going on in society.

Teaching buys you good karma. Share on XI have a great editor at Salon, Aaron Keane, who said, “Maybe you want to bring in even more famous mentor protégé conflicts.” What was great is it wound up making my piece more relevant and more topical, and maybe even able to help more people versus my own story. One of the things that’s good to do is find something in the news. I read five newspapers a day and I’m online a lot. There’s a lot of great magazines, movies, and TV shows. It’s a great excuse to binge-watch Netflix. There are also studies. You want to stay up on what’s going on because sometimes, that’ll give you a fresh angle or that’ll let you know what’s in the Zeitgeist. That’s an example of my memoir. It’s called The Forgiveness Tour and I was working on a piece about it.

Justin Timberlake apologized to Janet Jackson and Britney Spears. That plugged right into what I was writing. The idea that I played with is, “Is it ever too late to apologize, and does a belated apology count?” I did that for NBC.com. That’s one of the tricks that I use. Another trick is that you want to write the piece that only you can write. When I see pieces that I’ve seen before, I’ll say to my student, “I read that.” If it’s out there and I read it before, then you got to spend more time to find a more unique angle so that it’s not regurgitating something that’s already out there. You want to come up with something.

Do you find when it seems more generic like that, that the opportunity is most likely for the author to get more vulnerable?

Sometimes, it’s having an open mind and being flexible. I’ve had a lot of editors who come to speak to my classes. I have brilliant, amazing editors, including Dan Jones from Modern Love. I have some fantastic people who have given advice to my students at panels, classes, and seminars, and now Zooming in. A lot of other editors have said, “We have a moratorium on dead parents and grandparents’ stories.” What that means is that other editors, their bosses have said, “It’s too depressing. We’ve already done this. We don’t want to keep doing the same thing,” so they discourage those kinds of pieces.

This happened twice. I had two different students who were invested in writing about losing their mothers, which of course, is an important subject. What I said to them is, “It’s not that you can’t do it. You have to find a different angle so that you’re not telling the same story that everybody else has already told.” In one case, Elizabeth buried in the first draft of her piece was part of what was so painful about having her mother be sick when she was younger was that she knew her mother would never meet her husband. She was in a relationship, but she was trying to rush the relationship so that she could marry the guy so that her mother could be there for her wedding. I said, “Wow.” She wrapped the whole piece around that, especially for Modern Love, which is often about romantic relationships. She wrote that and that was a brilliant piece that got published.

A student of mine, Brian, wrote a piece and the first draft was about losing his mother. He mentioned on her deathbed, she made some reference that she wanted him to go back to Ireland to find their family because they were so well thought of there. That was interesting. I happened to ask him, “Did you ever go there? What happened?” He said, “Yeah, but what she told me was the exact opposite. We’re outlaws and criminals and they threw us out of the county.” I’m like, “Write that. That’d be sold to The New York Times Magazine.”

Quite often, it is collaborative. If you have mentors or teachers that you trust, if you’re open to maybe considering a less known angle, that’s something that could be helpful. I also push people to not only get more vulnerable but also to get more universal. “What’s the underlying question of what you’re writing?” For example, somebody was telling me a story and it was something to the effect of that. The thing that he hated most about his family was the thing that wound up saving his life.

I know with my forgiveness book and all the essays I wrote, I always tried to get back to the universal question, which was, “Could I forgive somebody who doesn’t apologize?” When I was writing Five Men Who Broke My Heart both in essays and in the book, the question was, “Did I marry the right person?” A lot of times, if you can’t necessarily go deeper and darker, if you could find that universal question that people will relate to, sometimes that’ll do it.

I have my book that’s coming out in January 2022. It’s a sequel to The Byline Bible and it’s called The Book Bible: How to Sell Your Manuscript―No Matter What Genre―Without Going Broke or Insane. In that book, I even have a whole section called Genre Fluidity. It’s similar to what I’m saying with essays. I can’t tell you how many times I started a project and I had this vision and it didn’t sell. Instead of giving up, I asked for feedback and I wound up switching the category and revising, and then it was able to publish.

It’s funny because I have seventeen books out of eight different genres. I was afraid that was making me a literary dabbler with no real expertise, but it turns out, it happens to be good for having an overview of publishing. For example, one of my students, Tony, wrote this fantastic piece. It was called This Father’s Day, I’m not getting my dad a present — I already gave him a kidney. It was this fascinating story and he wanted to write a memoir about it. His dad had been sick when he was growing up. His name is Tony Muchai.

What happens is I suggested, “Instead of an adult memoir, this would make a great middle-grade story where you could fictionalize it because you could change the age.” He was a little bit younger when he was faced with this horrible decision, which is, “I love my father, but I don’t want to do this life-changing surgery.” To me, since he’s still young, I wasn’t sure it would make an adult memoir because it’s fairly common and it’s not unheard of, but I have never read a kid’s book about that subject.

In my seminars, I talk a lot that I have several projects that started one way, and then because I was open to taking criticism and reimagining them, by doing that, I was able to then sell the project, sometimes to a top publisher. Of course, for your first draft or an essay or a book, do it exactly the way you want, but then if it’s not working or you’re not having luck externally, it’s a good time to go to an expert or somebody who knows the genre well.

Even before you’re testing it because it’s harder to go back and say, “I improved it. Will you look at it again?”

Once in a while, there is beginner’s luck. I have quite a few students whose very first clip was in The New York Times. Once in a while, you get a thing in your head. There’s the story that you want to tell and you write it. I’ve definitely had students whose first clip is The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal or The Washington Post. Sometimes, you get lucky. Writers tend to be stubborn, intense people. If somebody says to me, “I’m not taking your advice. I want to do it this way,” then I’m like, “Go for it and see what kind of response you get.” I’m not saying, “Send it to 50 people,” but, “Send it out a few times and see what kind of a response you get.” If it doesn’t work, then they come back and then I say, “Here’s what I would do.” By being open to criticism, sometimes that does the trick.

Especially when they’ve tried it their way.

Even though they say you can only have one shot, sometimes I’ve helped people revise a piece so extensively that the title, beginning, and focus are different. They have been able to go back to the same editor because it seems like a different piece. That can work. A piece that you wrote that you didn’t sell, if you Google and you look for topical beginnings, that could be a totally different piece.

You’ve got so many wonderful ideas. You can tell it has come from a lot of experiences and a lot of years of not only your own work but teaching so many people.

Truthfully, it took me a long time. It was a long struggle because I’m from Michigan. My family was not thrilled with my career choice and I couldn’t make a living. I had all these fucked up relationships and addictions that were getting in my way. I couldn’t make a living and I had all kinds of jobs. I wasn’t able to publish my first hardcover book. It came out when I was 43 years old. I moved to New York at twenty and my first real success happened when I was 43. What’s good about that for my students, I always joke, is that any mistake that could possibly be made in this career, I made it.

That might even explain the great reception that I’ve had. I noticed that my students, who are twenty and right off the top of the bat, started publishing everywhere and getting book deals, the knives come out and people resent that. It took me so long that people started to have pity or they started to feel like that’s the late bloomer angle. When you work for 23 years at something, there’s definitely the sense that you deserve success. Teaching buys me good karma because I have helped a lot of people also get published. When you’re helping other people, I’m not sitting around chasing after my own bylines.

Tell me a little bit more about your classes. Does a class include people writing all different kinds of genres or do your classes separate by what the focus is?

The great news for writers is that books are still happening. Share on XMostly they’re nonfiction. Truthfully, I was teaching specific classes at NYU, The New School, and Columbia. Usually, my big class was always writing for New York City newspapers and magazines. I would have editors come in. It’s what I write in The Byline Bible, but it was teaching people how to sell personal essays, service pieces, and op-eds. The shortest, quickest pieces that one could publish. We would bring in pieces and we would critique them. I did that in my private classes, too. When I went online after the pandemic, a lot of things changed.

Interestingly, I found even more editors were open to new material, which was exciting. I also found that maybe because editors were working at home or they were more busy, instead of writing the whole piece, which is what I recommend in The Byline Bible, I found quite a few editors who I work with who all of a sudden said, “I would rather get a pitch. Write me three lines about what you’re going to write, even if it’s an essay or an opinion piece, and let me tell you if I’m interested in this topic or which angle I would like, or how many words I would like.”

I also found it’s hard to go over 1,500-word Modern Love on Zoom. I was losing people. As an experiment, I tried to do a five-week online Zoom class I called a pitching class. When I ask people, what they hated the most was reading the long pieces out loud and what they loved the most was meeting editors. What I did was I tried one class and I thought, “Let me read pitches and let me have as many editors as I can come in.” I had fifteen editors come in a five-week class.

At the beginning of class, we’d go over the pitches, and then every week, I would bring in The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, LA Times. What was cool is that online, I could get anybody all over the country. Not only did it take off, but what was interesting was way more people were selling their work. I always had a lot of people that were publishing in my classes and the reason was that the editors were specific about what they wanted in their pitches. Also, the pandemic was so dramatic that even 14 and 15-year-olds or 25-year-olds or book authors or parents every day are going through such traumatic stories of like, “I had to move. I lost my job. How can I work when I have three kids I have to take care of? My uncle is sick. We have seven people living in my house. What do I do?”

People were writing all over the country, in the world. Suddenly, they are interested in international stories, so people started selling stuff left and right. I kept doing that, so that’s been exciting. The promise that I make is, “If you write a cover letter or a pitch letter and you send it to an editor, if the editor says yes, I’ll take it or even. I’ll look at this on Spec, then you send me the whole piece, and then I go over it on my own. Of course, I’m bringing in a lot of editors, so you could certainly try them.” That tends to work better because everybody in the class gets to meet each other, hear their ideas, and hear their pitches, and then you meet the editors.

What’s exciting is every week, we put the clips in the class. We put them on the chat. A week or two weeks before, somebody heard the pitch, and then they met the editor in the class and then there’s the piece. It winds up being an exciting and demystifying process, but it also means that the people in the Zoom from all over the country, some of them are in Europe, it’s midnight and in Asia, it’s 6:00 AM. They don’t have to sit through a 1,500-word piece and watch me edit it. They hear a three-line pitch. It’s a good thing to learn how to do it because a lot of people don’t know how to succinctly. You got to come up with a title. The Hollywood movie pitch makes it fascinating or interesting in a few short sentences. That’s one class I’ve been teaching. It’s been successful. I’m going to do it again. I was surprised because I usually don’t teach in August. I’m going away to visit my family in Michigan. Now, it’s on my computer, so I could do it.

People are publishing so much, so I’m going to do another one of those. Sometimes, I’ll do a one-shot seminar where people bring in one short piece under 1,000 words and I edit during the Zoom and tell them how to publish. I do those once in a while. I also do a how to sell your first book class and that’s been exciting because I could get editors and agents from all over the country to come in and answer questions about book projects. I could help people before they waste years. One book took thirteen years from start to finish, so instead of a book launch, it got a book mitzvah. I made so many mistakes.

What was exciting about the book class online is that it’s rare that you’d be able to talk to a seasoned author like top Random House or Counterpoint or these great editors, and then a top literary agent and ask them twenty questions like, “Does this make sense? Should this be a YA? Is this an adult memoir? Would it be better as fiction? Do I have enough of a platform for self-help?” Some people have gotten agents and a few people have gotten book deals since I started, so that’s exciting.

I’ve been trying to experiment with what I can help people with on Zoom, which is different. At the schools, we would have a fifteen-week class sometimes for 3 or 4 hours every week. That’s a little bit of a different story than a two-hour Zoom for five weeks, so I’ve been playing around. What I love about it is that the great news for writers is that books are still happening. Numbers went way up during the pandemic. Kids’ books are happening. Newspapers and magazines, even though some of them are in trouble, they’re still buying a lot of work for freelancers. It’s a certain work and you definitely have to be timely. You definitely have to be on the pulse of what’s going on or add wisdom to something they’re already covering. It’s been an exciting time for writers and artists.

Before I let you go, I have to ask you about this. You said in your book, The Byline Bible, that you have a course called Instant Gratification Takes Too Long. This sounds like the course that was made for me.

The overall method that I teach, I call it, the Instant Gratification Takes Too Long method, where the goal of all my classes and seminars is to write and publish a great piece by the end of the class or the seminar. I did my undergrad and graduate degrees, so we’re talking six years of intensive study. I came out not even knowing how to write a cover letter to send out any of the work. Of course, I can’t compete with Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning writing teachers, but what I can do is I could teach the one thing that nobody teaches, which is how do you get out there? How do you market the work?

I have a degree in Poetry and I’m a good critic. My own book, at a certain point. It’s not that they don’t care about the literary merit. If you could combine the literary merit with a little bit of business savvy and an overview, I’ve had a good dual career for a lot of years now, so then it gets exciting. I say to my students, “Three pages can change your life.” That’s the overall method. Everything that I teach, I have that in mind as a goal. I’m goal-oriented. There’s definitely a goal. If somebody’s beginning or they want a more experimental class, I know tons of brilliant teachers in all genres, so I could recommend teachers that are slower. It’s that nobody teaches the stuff that I wanted to learn, which is what do I send out to who? How do they buy it? How do I get money? How do I make a living doing this? How do you build on it?

That’s so important because if it doesn’t get sold and it doesn’t get out there, then you’re writing to yourself, which isn’t the same kind of experience.

Nobody was doing this and this is what I wanted. There’s a line and a poem about how you become what’s missing.

How would our readers find you?

By the way, I have an online launch event for my co-authored book, World In Between, on July 27, 2021. I’m going to send you a flyer for it. Shakespeare and Company is sponsoring it, but it’s online. It’s an hour panel where I have amazing editors, agents, and three students who, interestingly, all launched their books with short pieces in the Washington Post and New York Times. That’s exciting. The price of a book is $15 to get into. It’s the next thing that I’m doing, which is exciting.

If they want to email me, ProfSue123@Gmail.com, or you can go to my website. I’m constantly updating all the events that I’m doing, all the panels, the classes, and stuff like that. Since I have to cold call so many people or cold email somebody, I promise I always get back to people. If anybody emails me, I absolutely get back to them. I love social media. My students taught me how to do it. You can follow me on Instagram, it’s @ProfSue123. It’s @SusanShapiroNet on Twitter and Facebook. I post everything on LinkedIn. I post all my events and stuff on all their social media platforms. That’s exciting for me, especially now that everything’s online. I get students from all over the globe.

I thank you for sharing so much wisdom.

I’ll send you a flyer for the upcoming event.

Thank you. I appreciate you coming on. Thank you.

Thank you.

Important Links:

- Five Men Who Broke My Heart

- Lighting Up

- Unhooked

- The Forgiveness Tour

- The Byline Bible

- Susan Shapiro

- World in Between

- Abby Sher

- Viking Penguin

- NBC.com

- The Book Bible: How to Sell Your Manuscript―No Matter What Genre―Without Going Broke or Insane

- This Father’s Day, I’m not getting my dad a present — I already gave him a kidney

- World In Between

- ProfSue123@Gmail.com

- @ProfSue123 – Instagram

- @SusanShapiroNet

- Facebook – Susan Shapiro

- LinkedIn – Susan Shapiro

About Susan Shapiro

Susan Shapiro is the bestselling author/co-author of 17 books her family hates like Five Men Who Broke My Heart, Lighting Up, Unhooked, The Forgiveness Tour, the writing guide The Byline Bible and World In Between. She teaches her “instant gratification takes too long” courses at The New School, NYU, Columbia University and in private classes & seminars – now online. Follow her on Twitter at @susanshapironet or Instagram at @Profsue123.

Susan Shapiro is the bestselling author/co-author of 17 books her family hates like Five Men Who Broke My Heart, Lighting Up, Unhooked, The Forgiveness Tour, the writing guide The Byline Bible and World In Between. She teaches her “instant gratification takes too long” courses at The New School, NYU, Columbia University and in private classes & seminars – now online. Follow her on Twitter at @susanshapironet or Instagram at @Profsue123.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join The Author’s Corner Community today: